Think about policymaking, and it’s easy to picture the House of Commons. Green seats, ayes to right and noes to the left. A lot of passionate sneering and cheering.

You might also think of climate activism and conjure an image of Greta Thunberg with her placards, Just Stop Oil, or Greenpeace and the history of the Rainbow Warrior boat.

But businesses also have a crucial role to play in society and in protecting the planet. Corporate accountability not only encompasses financial responsibility towards shareholders, but it also includes social responsibilities towards people and the environment.

This is especially key for those who are interested in ethical investing, but also for ensuring that businesses do not suffer operationally and economically as a result of environmental damage.

At Blue Earth Summit in Bristol speakers from a range of different sectors highlighted both the good work that is being done to provoke change within corporations, but also how businesses are holding themselves liable and being held accountable more widely.

Can businesses be activists?

Unlike traditional street activists, professionals face constraints such as KPIs and deadlines. However, there are those who believe, and indeed show that changing the game can happen from within.

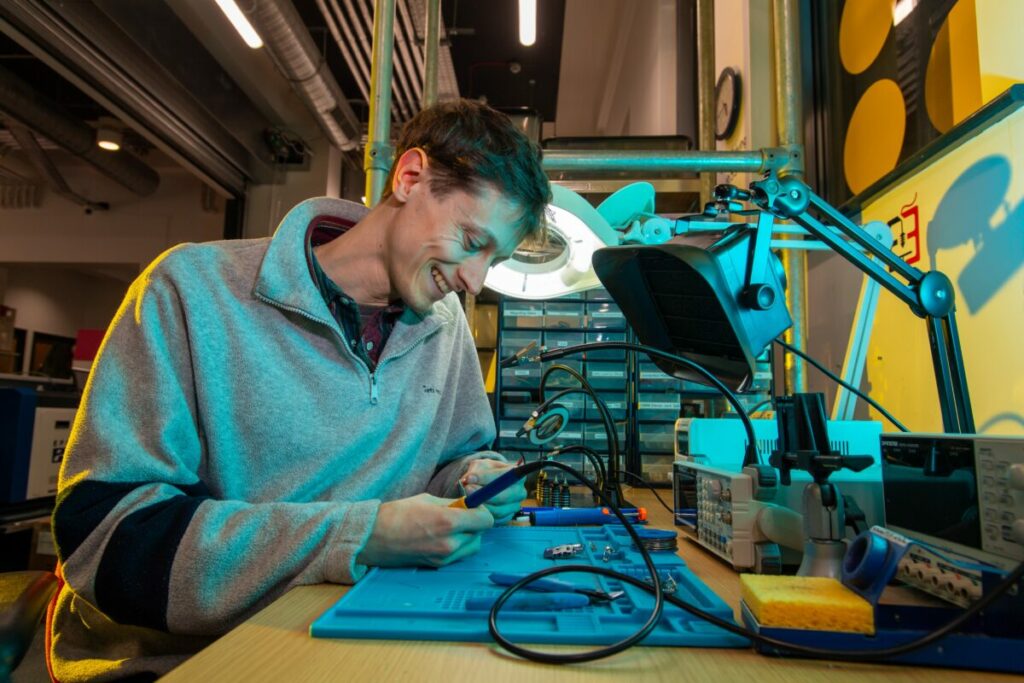

Fairphone is one business which adopted a disruptive model to help change things from the outset. Designed in order to minimise the use of materials from conflict ridden regions and to lower the environmental footprint of the smartphone industry and known for their sustainable approach to tech, the company has existed as a social enterprise for thirteen years.

Speaking on a panel about corporate activism co-founder Tessa Wernink spoke about what inspired her and others to create business models like this: “Individuals started running businesses from the perspective that they were surprised and flabbergasted that businesses run the way that they do and they started setting up purpose driven businesses.”

“I think we can learn a lot from the way that businesses have been set up based on inquiry and roll modelling what businesses could be like, and they really were set up to disrupt industries from the inside”.

She continues, “I think as the population or the demographics within businesses change, we have a lot of people who have grown up with climate anxiety come into their businesses. And we might think that you know, employee activism isn’t real but if you look at some of the statistics, there have been a lot of studies over the past couple of years

“Activism isn’t always about being the one who speaks up and abusing the limelight, when it comes to lobbying in particular, I think that there’s a lot of fact finding that needs to happen.

“But there’s a lot of self sabotage from big companies, intentionally or unintentionally. They might be giving money to lobby for anti-climate legislation,” she says.

She adds that sometimes lobbying isn’t so explicit, “Are you a member of trade associations that are different from who you are lobbying with? So I think that the first thing their employers really need to do is develop that communication and then it’s recurring, how can we organise and start influencing”.

Subscribe to Sustainability Beat for free

Sign up here to get the latest sustainability news sent straight to your inbox everyday

The quest for a circular and regenerative economy

Andres Roberts co-founder of Bioleadership Project, which works with partners from Lush to Aviva Investors to Patagonia, in order to look at more regenerative ways of doing business speaks about the nature of responsibility beyond simply making a statement.

Discussing his work with CEO of clothing brand Patagonia, Roberts highlights the importance of dropping a perfectionist mindset, “For me what’s important is it’s something that Patagonia demonstrate very, very well is, what they say is well, what they speak to is let’s be honest about what’s needed. That regenerative is fair. And in their own words we’re not a regenerative business, we’re not a sustainable business. We’re trying to be a responsible business”.

Discussing his work with CEO of clothing brand Patagonia, Roberts highlights the importance of dropping a perfectionist mindset, “For me what’s important is it’s something that Patagonia demonstrate very, very well is, what they say is well, what they speak to is let’s be honest about what’s needed. That regenerative is fair. And in their own words we’re not a regenerative business, we’re not a sustainable business. We’re trying to be a responsible business”.

He also highlights the importance of “vulnerability” and the need to speak to the fact that we’re not there yet.

Meanwhile founder of sustainable handbag company Elvis and Kresse, Kresse Wesling adds, “I think about it from a design perspective.Yes we design handbags but the more important thing we design is the business, the way it’s structured what it does and the farmer is a key part of that.”

But what happens when businesses fail at accountability?

Client Earth CEO Laura Clarke highlights the importance of the law and developing new understandings of risk beyond traditional fiduciary risk (which normally entails the responsible management of assets).

While activists within corporations face limits imposed by their working day and need to hit targets, Client Earth is run entirely on the basis of philanthropic donations so can choose which cases to take to court. The cases they hold include cases against the UK government, to cases against Shell or Belgian National Bank.

Whilst she is in the business of bringing claims to court, Clarke highlights that she doesn’t discount the good work being done and seeks to use the law to make businesses more aware of their responsibilities.

She splits the risk for corporations in to three elements, “It’s the physical risk of rising sea levels, of extreme weather events that could damage your investments and infrastructure. It’s the regulatory transitional risk and the risk of litigation”.

“If you’re looking at the long term sustainability of your company you cannot discount the climate”.

She highlights the challenges of taking on power, “The big corporations have got such an army of lawyers thinking about their interests, not thinking about long term sustainability, and so we’re thinking about what does the earth need”.

“But mindsets are changing the question is just, are they changing fast enough? And how can we with the law set the right precedents but accelerate that behavioural change?”

Do we need to shift how we think as a society?

In his keynote speech acclaimed historian and writer David Olusoga took to the stage to raise the social divides that impact how people interact with nature, “This gathering and gatherings like it simply don’t reflect the ethnic make up of the cities in which they take place”.

In his keynote speech acclaimed historian and writer David Olusoga took to the stage to raise the social divides that impact how people interact with nature, “This gathering and gatherings like it simply don’t reflect the ethnic make up of the cities in which they take place”.

He went on to highlight that a survey by Natural England back in 2017 found that “while 44.2% of white people had an opportunity to visit and enjoy time in natural spaces in the UK, only 26.2% of Black people were able to do this”.

He pointed to the history of a gated countryside, Olusoga highlighted how traditional ways of practising farming and who governed the land have helped cement this divide.

Regardless of whether it’s activists working within a corporate setting, or outside of it as Client Earth do, accountability has never been more key. As Olusoga highlights, the climate crisis is also a social and economic one, which raises questions of how we can use our space more fairly – in the interests of all people and the planet.